Artificial intelligence is the technological breakthrough defining the cultural zeitgeist of modern times. Go anywhere on the internet and you’ll have a good chance of running into AI. From customer service chatbots to synthesized pictures on Facebook, it’s hard to miss. With the size of its impact comes an even larger debate on its ethics and appropriate uses. The ones I find most interesting have to do with AI art. But before we can answer the big questions, we must build a solid foundation of understanding. In the immortal words of Elvis Presley, “Don’t criticize what you don’t understand, son.”

What is AI?

Since I am no mathematician or computer scientist, we’ll be leaning heavily on those who are. The best general definition I could find was from Louisiana State University. My criteria for best being clarity for lay people (most of us), and least likely to have a conflict of interest. Their definition is as follows:

Artificial intelligence (AI) is an interdisciplinary field combining mathematics, statistics, cognitive science, and computing to solve complex problems using large datasets and high-performance computers.

Within AI, machine learning and deep learning are key subfields. Machine learning involves algorithms that enable systems to learn from data, while deep learning, the most advanced form, closely mimics human intelligence using neural networks.

I think it’s extremely important to point out that they say it “closely mimics human intelligence” and not that it fully recreates it. It is also worth mentioning that machine learning is the type of AI used for generative AI models like ChatGPT. MIT describes this kind of AI as a system “that learns to generate more objects that look like the data it was trained on.” However, the lines are not exceptionally clear on where something changes from machine learning into the more complex deep learning so let’s treat them both as possible sources for AI art.

Deep learning does currently exist. Its main uses are in the health field. Most of these articles have fun, breezy titles like “Deep learning network enhances imaging quality of low-b-value diffusion–weighted imaging and improves lesion detection in prostate cancer” and “Multi-convolutional neural networks for cotton disease detection using synergistic deep learning paradigm.” There are other uses as well, though, like facial recognition and self-driving cars.

So is the machine uprising coming? No. Deep learning is actually the rebranded name of neural networks. A computer science concept “modeled loosely on the human brain.” (Notice how the wording again won’t say it replicates a human brain?) What this kind of AI excels at is processing massive amounts of data and training itself on the patterns therein. It then uses what it has found to process new data to find similar patterns. Thus making it a highly effective tool for analyzing lots of complex data, the kind you might see in studies of the human body.

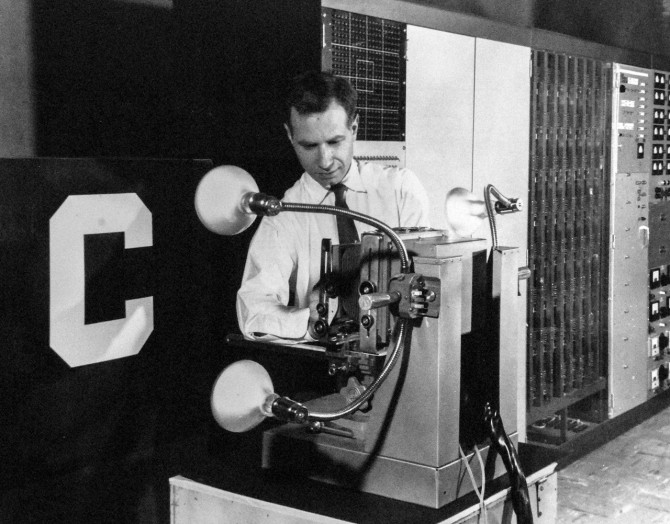

It may shock you to know that the first application of a neural network was actually in the ’50s. It was created in a massive, 5 ton computer that occupied an entire room. This giant computer was dubbed Perceptron. It eventually “learned” to distinguish whether punch cards had a mark on the left side or a mark on the right side.

Frank Rosenblatt, Ph.D., Inventor of Perceptron

Unfortunately, Perceptron’s advances would not bear great fruit for another half a century. The field was largely silent until recently. Now we are seeing AI technology progressing at breakneck speed. So what does it all mean for AI art? Well before we can really get to the bottom of that question, we need to look at the latter word in the term AI art.

What is Art?

This is the deeper question wherein the controversy truly lies. When searching for a definition, I find that many people get bogged down in prescriptive definitions, often relying on the subjective quality and value of different art. However, I would posit that the sheer imposition of such restrictive rules usually speaks to a person’s lack of creativity. The irony being that art, by my definition, is simply any intentionally creative process.

It is key to note that art is not necessarily the product. Therefore two identical things could vary in their classification of being art. For example, the dinners that my husband hurriedly throws together on a weeknight just to make sure our kids are fed are not art. However, the dinners my husband cooks that take all Saturday afternoon, where he has searched for several recipes to tie together, gone to the store to carefully select myriad ingredients that’ll bring out each other ingredient’s best qualities, and thoughtfully redirected when a flavor is not quite what he wants, are art.

These examples are quite obviously of varying calibers, but let’s now complicate things more. Say that one of my husband’s Saturday night dinners turns out to be a huge hit with the family so he makes a note of all the ingredients he used and the modifications he made to recipes. Then, on a future weeknight, he whips out the same dish, following his previous notes to a t because he doesn’t have the mental energy to come up with more modifications. The dishes themselves would be impossible for a 3rd party to distinguish, yet I would argue that one of them is art while the other is not.

Now let’s dive a little deeper. In our previous example, the repetition of a task stripped it of its qualification as art. However, sometimes the art lies in the tedium. Let me explain. I love to knit. I find the repetitive motion to be extremely soothing. Before my carpal tunnel got particularly bad, I would sit for hours on end doing the same few tasks ad infinitum, or at least until some responsibility drew me away. I’m also particularly slow at knitting so I would see very little progress during these hours-long stretches. The thing is, it didn’t matter. The beauty was in the experience itself and my ability to be fully mindful and patient.

Here you might be saying, “But Lennox, your definition of art is being intentionally creative regardless of qualities like beauty, yet you also say your knitting was art because of the beauty in the experience.” To which I would say: yes. Is your head starting to hurt yet?

My knitting is art because I found my unique satisfaction in the act of creating. Not everyone would enjoy knitting in the way that I do. It is an utterly human experience to feel differently than others. To have preferences and opinions shaped by a mysterious combination of nature and nurture. To have likes and dislikes that align and vary with those around us. Making a choice can be creative if you decide it is. Anything you do or create is art if you have chosen for it to be art.

AI Art

Ok, so what does this all really have to do with AI art? Well I submit that art is an embodiment of human experience and choice. Therefore the deciding factor in the argument of whether or not artificial intelligence can create art is if AI can experience and choose.

The “Chinese Room” Argument

Let us use our imaginations for a moment. Something we are uniquely positioned to do. Picture a room, its walls lined with boxes. Within the boxes are countless sheets of paper filled with different Chinese symbols and English instructions on how they should be strung together, but, importantly, not their definitions or any mode of translation.

Now imagine that in the room there is a person who only knows English and a piece of paper with a question written in Chinese symbols. Given enough time, that person could formulate a written answer to the question based on the instructions within the room that would read as sensical and fluent to a native speaker.

Here’s the question: did the person in the room understand the question and subsequent response? John Searle, the inventor of this thought experiment, says no. He argues that true artificial intelligence is impossible because, despite the programming (boxes in the room) and the output (an answer that makes sense to the reader) in response to the input (question on paper), there is no true understanding.

No amount of logical aggregation and pattern recognition can recreate the human process of understanding. Furthermore, no true choice is being made by following rules and programming. So the AI we have cannot truly create art by the definition of human experience.

The Threat of AI Art

Perhaps you think that regardless of my esoteric definition of art, AI art still poses a threat to artists. You might say that despite its inability to feel or choose, AI technology is moving so rapidly that it will undoubtedly outpace humans. In the realm of profit, I could agree, but no more than any other person or system created within capitalism. For instance, I’m not convinced that AI music is any more of a threat to a musician’s ability to establish a profitable career than Spotify’s algorithmic playlists, predatory 360 contracts, nepotism, or even just being born ugly.

Outside of profit, though, I’m not sold. We’re all familiar with Picasso’s famous quote, “A good artist copies, a great artist steals.” Since AI can only combine what is fed into it, or mimic the patterns of the data fed into it, it can’t really create anything original. Its output is merely some version of copying. While human artists are certainly influenced by those who came before them, many of them add their own touch. It is the newness they inject into their work that makes great art.

What AI Can Never Do

My favorite painter of all time is Salvador Dalí. When I first laid eyes on his work as a child, I was blown away. I had never seen anything like it. It turns out that his bizarre style had been groundbreaking in his time as well. His contemporaries all pursued the same goals of hyperrealism that had long been the aim of painters. However, Dalí, and the other members of the surrealism movement, ran the other direction. He saw the limitless possibilities for paintings that could reach beyond the mundanity of reality. That is what made his art exceptional.

Salvador Dalí’s Persistence of Memory (1931)

In music there is not shortage of similar examples. Stravinsky’s infamous Rite of Spring was so dissonant, a stark contrast to all the musical works preceding it, that its premiere incited a riot. John Cage’s 4’33 turned the very concepts of silence and music on their heads and ended with a near empty auditorium the first time he performed it because people were so shocked and offended. N.W.A.’s Fuck Tha Police brazenly called out law enforcement and police brutality in such an unprecedented way that the FBI issued a notice to the band’s record label urging them to stop performing the song. (Spoiler alert: they didn’t.)

You may also note that on top of disrupting norms of art, many of these artists disrupted the norms of dominant society. The sheer power of art born from the indomitable human spirit and its pursuit of a greater world is impossible for a machine to reproduce. As a matter of fact, AI is particularly adept at homogenization, stripping the niche individualities from the complex data fed into it. Patterns require repetition. In other words, the more common something is, the more likely AI will prioritize it.

Additionally, the art that we so often consume is just the tip of the iceberg. To water down art to just its final product fails to recognize all the other beautiful parts. There are lifetimes that exist under the surface. AI art is a thin veneer that peels away to reveal nothing.

I can only fully speak to my experience, but behind my art, regardless of your thoughts on its quality, is a rich human experience. That is something that AI art could never threaten. AI art cannot take away the rush I get from creating the perfect synthesizer sound after hours of fiddling with oscillators and filters. AI art cannot rob me of the catharsis of weeping while writing lyrics that finally express a pain I’d been holding onto for years. AI art cannot evoke the emotions in me that the creation of art can.

So who cares what AI produces? It could never produce the same visceral excitement in my kids as when they ask to hear “Mama’s music.” Nor could it produce the fulfillment that request gives me.